I believe the novel genuinely delivers what's on the cover (which we all know is not always the case). I hope you agree:

|

The countdown in my head has started. It's 50 days until my historical fantasy Conquist is published by Roundfire Books. Although I can hardly wait for publication on 1 September after all the years I've lived with this novel, in a way I don't really want the days until then to rush by. It's not just that I'm very aware that many of the promotional hard yards are pre-publication—there's still a lot to do over the next 50 days. I also want to savour the time before reader reality inevitably bites. At the moment, it's still all about possibilities.

I believe the novel genuinely delivers what's on the cover (which we all know is not always the case). I hope you agree:

0 Comments

Does the wave of AIs with natural language capabilities herald the end of fiction as we know it? If you think that the question is absurd, you haven’t really got to grips with the sorts of things that GPT and other generative AI software can do.

The American science fiction magazine Clarkesworld has the following message on their website: Statement on the Use of "AI” writing tools such as ChatGPT We will not consider any submissions written, developed, or assisted by these tools. Attempting to submit these works may result in being banned from submitting works in the future. Editor Neil Clark announced in February they were temporarily closed to submissions because of the sudden 38% increase in what they called ‘AI spam’ submissions. He says he can spot them because there are some obvious patterns. Sheila Williams said Asimov’s experienced a similar increase. She says ‘The people doing this by and large don’t have any real concept of how to tell a story, and neither do any kind of AI. You don’t have to finish the first sentence to know it’s not going to be a readable story.’ Here are some questions to think about regarding the future of fiction, with a stab at the answers based on my current understanding: Who owns the copyright of AI-generated fiction.? Well, either no one or the humans who wrote the material that the AI was trained on. The words aren’t actually copied from anywhere. The AI generates words which it has statistically predicted from the Web as a response to an instruction and rephrases the material. The words have never been put together in exactly that combination before. Who can pretend they have actually written a work of fiction that was generated by an AI? Er… anyone can. Maybe at this still relatively early stage of these AIs, you can tell (or think you can tell) that the work wasn’t written by a human, but you could never be absolutely certain. (And the AIs will only get better.) Ironically, one criteria you could use is to see if the work has no grammatical errors or incorrect word usage—but of course, that could also be a sign of a highly competent writer. Plagiarism-checking software has been around for some time, so some sort of AI-identifying software is possible, but will it be good enough to keep pace with improvement in AIs? Can AI-generated fiction be truly original? Science fiction writer Ted Chiang sees a human author's first draft as often an original idea, badly expressed, while the best an AI can generate is a competently expressed, unoriginal idea. One way to look at what the AI does is create an amalgam of photocopies of original documents. Originality is always lost through the photocopying process. On the other hand, there are also lots of unoriginal human fiction authors around. Being truly original is a high bar that few writers achieve. And yet, each human’s life is unique, so the perspective they bring to a work of fiction has originality as its seed. The best writing comes from skilled writers who can turn that unique perspective into fiction. An AI can’t do that. Can AI generate fiction that ignites an emotional response in the reader? Authors create emotional responses through combinations of words. If you ask an AI to write a horror story, I suspect it can glean how to achieve the fear effect with all the sources available to it. Can it create fiction that makes the reader laugh? Maybe: puns can be generated, jokes have structure, certain situations are inherently funny. What about making them cry? Who knows? I’m sure someone will put that to the test. Can an AI generate the sense of awe that a great work of science fiction or fantasy can? I suspect not, but then as a writer of speculative fiction I’m biased. The most powerful emotional response to a work of fiction, however, goes deeper than fear, humour. sadness or awe, it’s the sense of human connection that the reader feels with the words spun by the writer. An AI can’t do that. How much instruction would a writer need to give an AI for it to generate a publishable work of fiction? Minimal instructions will most likely result in a bland, uninteresting work that wouldn’t make it to publication. However, if you are a meticulous planner, then including detailed plot outlines, world build and character descriptions could result in something publishable. The 'garbage in garbage out' rule applies. The success or otherwise depends on the quality of the input. As every planner knows, there is an enormous amount of time and effort needed before the writing begins, so the success or otherwise will depend on all that work. If you are more of a panster (that is, fly by the seat of you pants), then the joy of the writing is in the discovery, so you probably would see any point in using AI to write fiction. Either way, the AI may end up being some assistance to some fiction writers, but it can’t replace them. What are fiction writers feeling about the potential impact of AIs? They’re not happy. I’ll give just one quote. This is from British-Australian dark fantasy author, Alan Baxter: ‘In a world where people are still cleaning toilets and working in mines, I can’t believe we’ve got the robots making our art and stories. I thought robots were supposed to do the shitty jobs to allow more people to pursue their passions. AI is simply a hideous and well-focussed encapsulation of capitalism at the expense of humanity.’ What’s the most optimistic outcome of AIs for fiction writers? AIs could end up being support for fiction writers rather than making their life harder. At some point it will be possible to feed an AI your novel manuscript and ask it to generate a synopsis of your novel to a set word count, taking on a burden that many writers loathe. If it could, for example, provide a narrative description f a particular place at a particular time in history, it would short-circuit a considerable amount googling and other research. The AI could also provide some required technical information in natural language specifically catering to non-specialist readers which can be adapted for a work. We all know the definition of science fiction is notoriously hard to tie down. One way of looking at it is as the form of fiction that speculates on the impact of actual or imaginary science and technology. While the world heralds the latest technology and grapples with its consequences, the science fiction world has already explored its potential impact on individuals and society. With the recent explosion AI systems into our awareness, we are in a truly science-fictional moment in history: here is technology that science fiction writers have speculated about for decades. While this is either ecstatically or shockingly new for most of the world, to science fiction readers and writers it’s a matter of reality catching up to our imaginations. As a collective, we’ve already thought about where AI could take us. With anything startingly new, there are the true believers, nay-sayers and head-in-sanders. For those of us into science fiction, this is simultaneously an ‘Oh, wow!’ and ‘Oh, shit!’ moment. We can see both sides. We’ve already pictured the potential future in our imaginations. So, let’s prepare ourselves for the exploration. We live in interesting times. This blog appeared in a different form as the Editorials for Aurealis #158 and Aurealis #159. We are living in the golden age of fantasy prequels. At least on screen. I’m usually a little wary of prequels. To me, they suffer one big handicap compared to non-prequels: we know the ending. Take away the tension of an uncertain ending and the narrative drive can falter. There are ways around this problem but, in my view, prequels are behind the eight ball from the start. The prominence of The Rings of Power (2022–) and House of the Dragon (2022–) has created a lot of discussion on what makes a good prequel. Film critic Steven D Greydanus refers to Shrinking World Syndrome, saying, ‘As a franchise plays out, very often, the more the mythology expands, the smaller the universe gets. Previously unconnected characters and events that gave the fictional universe a certain expansiveness are increasingly tied together for dramatic effect, until the whole story is about a small group of closely connected individuals.’ There’s no doubt that great prequels expand the universe rather than repeat it. Given this criteria, Molly Templeton in her Tor.com article argues that The Rings of Power is coming up a little short so far. She says, ‘With three thousand years of history to explore, we’re getting the same familiar faces again—Galadriel, Elrond, Gandalf, Sauron. Is the world really so small that these are the only ones with stories worth telling? The best parts of the show, for me, are Nori and Adar and Bronwyn and Arondir—they’re the ones who make the world feel larger and richer and give the illusion that things are happening even in the places where there isn’t a camera to see it.’ In defence of the writers, however, you could argue that the longevity of the main players in the Tolkien universe inevitably requires that they be prominent in The Rings of Power prequel. According to some, the House of the Dragon has a different problem. With its concoction of murder, revenge, infighting, incest and dragons, does it appear to be a little too familiar to be considered a truly great prequel? Sure, we’re getting more dragons and more Targaryens, but is simply more what good prequels are about? Is it repeating rather than expanding the universe? Still, the revenge cycle worked brilliantly in Game of Thrones (2011-2019), so why not keep it cycling? In the end, the overriding hope for fans is that House of the Dragon provides redemption after the much-maligned ending of Game of Thrones. Give us more of the same, but with a better ending.  What about prequels in fantasy books? The first prequel I read was C S Lewis’ Narnia book The Magician’s Nephew (1955). I remember trying to get my head around the bewildering fact that the book about the origin of Narnia—which included an explanation of how a London lamppost came to appear in a Narnian forest in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)—could be the sixth book in a seven-book series. Publishers have since released the series in chronological order so that newer generations will read The Magician’s Nephew first. The interesting thing is that The Magician’s Nephew prequel works either way because it is self-contained. Perhaps another criterion for a great prequel is that it can be read independently.  A more recent prequel I’ve read is Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage (2017), the first book in The Book of Dust trilogy. Philip coins the term ‘equel’ for this novel, describing it a companion work to his His Dark Material trilogy that can be read on its own. Whatever the case, it seems to also meet the other criteria for great prequels by expanding our understanding of the divinatory alethiometer and the enigmatic particle Dust. Pullman manages to maintain high levels of tension, despite the fact that we know the baby Lyra will survive, by focusing the story on a new character Malcolm who is trying to save her. One thing isn’t in doubt: when a prequel is done really well, it can be immensely satisfying.

A version of this blog appeared in Aurealis #157.  What’s the longest SF novel you’ve read? In a genre known for worldbuilding and galactic-size plots, SF is well-represented in the long novel stakes. Still, I’ve always been a little reluctant to tackle really long novels. They better be bloody good!

Here are some of the most well-known SF door-stoppers: Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is up there at 470,000 words. It was the very first mega-long book I read. I was twelve years old. Although I was a voracious reader, the books I had read up until that time were more the Narnia and Enid Blyton size. Yes, The Lord of the Rings created the fantasy trilogy phenomenon, and you can quibble that it’s really three books, but it was only released in three volumes originally because of the paper shortage after World War II. I read it in the intended form and in which it has generally been published since, which is as a single book. It's often cited as the longest genre novel of all time—but it isn’t. It is pipped by Stephen King’s The Stand, which I’m reading at the moment, at 472,376 words. Interestingly, the original published version in 1978 wasn’t that long at 322,000 words, but the Kingster decided to publish the version he had originally written before his publishers made him cut it. I’m really enjoying it, but it’s taking me a lot longer to get through because life seems to get in the way now more than it did when I was twelve. I wonder whether he knew that by publishing the extended version, he would be overtaking Tolkien? King has form in the door-stopper genre: It was 445,134 words. George R R Martin cracked the 400,000-word mark twice in his Song of Ice and Fire series with A Storm of Swords at 422,000 words and A Dance with Dragons at 420,000 words. Apparently, he was worried about the length in the earlier books in the series and took great pains to keep them down to a modest 300,000 words by moving chapters to the next volume. That process will eventually catch up with you, I guess. Since we’re still waiting for the series conclusion, I think it’s too early to discount his efforts in the largest genre book of all time stakes. Others in the over 400,000 category are Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon (415,000), Diana Gabaldon’s An Echo in the Bone (the seventh Outlander novel) (402,000), and Patrick Rothfuss’ The Wise Man's Fear (400,000). But if you’re looking for the longest SF novels of all time, it can sometimes come down to genre definitions and whether you only include best-sellers. Here are some of the contenders: Tad Williams’ To Green Angel Tower (520,000), Diana Gabaldon’s The Fiery Cross (502,000) and A Breath of Snow and Ashes (501,000), Mary Gentle’s Ash: A Secret History (500,000), and Brandon Sanderson’s Oathbringer (495,000). You have to admire writers who can produce high-quality writing over such enormous word lengths. But does size ultimately matter? I'll explore this in part 2.  How much does luck play in fiction publishing? Does the cream inevitably always rise to the top while the crud sinks? You might be surprised by the views of the CEOs of the major publishing companies. Many of you would be aware of the proposed $2.17 billion purchase of publishers Simon & Schuster by Penguin Random House which would have created a publishing giant with 70% of the US literary and general fiction market. The merger of the two publishers would have reduced the five major publishers to four—the other three being HarperCollins, Hachette Book Group and Macmillan. The US government didn’t think the purchase was a good idea for authors or readers and said it would ‘substantially lessen competition,’ so it blocked the merger in November. What’s fascinating is that the testimony in the court case this year has laid bare some of the mechanisms of how traditional publishing actually works. What caught my eye was a comment from the Macmillan CEO Don Weisberg, who when arguing against the merger, described publishing as ‘a business of gambling’. What made it even more interesting was that Penguin Random House CEO Markus Dohle arguing for the merger compared Penguin Random House to Silicon Valley ‘angel’ investors, saying, ‘We invest every year in thousands of ideas and dreams, and only a few of them make it to the top… Each book is unique and there’s a lot of risk.’ So the two opposing sides actually agree on the importance of luck in picking bestsellers. The mega-selling SF author Stephen King testified as a witness for the government in the case, arguing that mergers in the publishing industry harm authors and are bad for the industry. He said that when he was an unknown author in the 70s, there were hundreds of imprints, competition was fierce, and he didn’t need an agent. Since then, the number of publishers has shrunk and with them the size of author advances and opportunities for new writers. ‘There comes a point,’ he said, ‘if you’re very, very, very fortunate, that you can stop following your bank account and follow your heart.’ In fact, Stephen King deliberately tested the importance of luck in publishing by writing five novels under the Richard Bachman pseudonym. In the eight years before Bachman was outed, Stephen King was a mega-seller while Bachman was a nobody. After he was outed, the Bachman book sales rocketed, quickly reaching 3 million copies. In his introduction to The Bachman Books Stephen King ruminates on the role of luck or accident in his own publishing success: ‘The fact that Thinner did 28,000 copies when Bachman was the author and 280,000 copies when Steve King became the author might tell you something, huh? Part of you wants to think that you must have been one hardworking SOB if you end up riding high in a world where people are starving, shooting each other, burning out, bumming out… but there’s another part that suggests it’s all a lottery, a real-life game show not much different from Wheel of Fortune or The New Price Is Right.’ What role does luck actually play in the publishing industry? Food for thought for all of us. This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #156. Have you ever wondered how different screenwriting is to writing novels or short stories? After concurrently writing a screenplay and novel version of my conquistador fantasy short story ‘Conquist’ (Dreaming Again, Ed. Jack Dann, HarperVoyager), I’ve got a pretty good idea. The two are very different. Obviously, there are similarities. The plot, the characters and the dialogue are important to both. But it’s the differences that strike you when you switch from one to the other. In my experience, the two writing styles often interfere with each other. Let’s start at a basic level. The action in screenplays is always in the present tense, while the most common tense used in novel narratives is the simple past tense. This alone can drive you a little nuts when switching between novels and screenplays. Whatever tense you’re currently writing in becomes habitual; it feels natural and intuitive. You do it without thinking. And worse, unless you deliberately read for tense, you simply won’t catch all the times when you’ve incorrectly got past tense in the screenplay action or present tense in the novel narrative. And, strangely, when you make the change, at first it feels wrong somehow. The number of words you have to play with in a screenplay is far less than what you have at your disposal in a novel. My screenplay for Conquist is around 22,000 words while my novel version is 86,000 words. In fact, the movie industry doesn’t even talk about the number of words. It talks about pages. The average movie screenplay is around 110 pages, which are formatted in such a way that a page represents around one minute of screen time. So, the 110 pages represent just under two hours, which is somewhere near the average length of a movie. You need to be aware, though, that this restriction on the number of pages only really applies to spec scripts—that is, the ones that are written on-spec without a contract. If you’re Tarantino, you can go for broke. The word limits in a screenplay affect all aspects of the writing. To come in at 110 pages, you need to have extreme focus from a plot point of view and write with a maniacal tightness. While novel writers obviously also need to make choices about what to include and what to cut, screenwriting forces you to dial this process up to warp drive. There’s nowhere to hide. Going over 120 pages, for example, can often mean you’re dismissed as an amateur before you even get to first base. And if you think manuscript requirements for novels or short stories are over-prescriptive, you ain’t seen nothing yet. The formatting requirements of screenplays appear overwhelming at first. I don’t know how they managed it in the Golden Age of Hollywood, but I wouldn’t even think of writing a screenplay without a software package like Final Draft. So how do you turn a novel or short story into a screenplay which actually becomes a movie? Well, clearly, one way is to first get your story published in Aurealis! C S McMullen's story ‘The Other-faced Lamb’ that appeared in Aurealis #82 has been released as a major motion picture The Other Lamb.

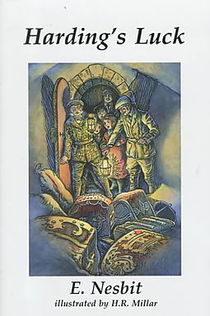

This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #124.  We all have books that we read when we were younger and which led us into fantasy or science fiction or whatever genres we choose to spend the bulk of our time reading as adults. These are often called gateway books, those novels that opened up reading for us. While some of my gateway books into fantasy include staples such as The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings and the Narnia series, I would also count a handful of more obscure books as my way into fantasy in particular. I suspect we all have some of these lesser known books in our reading past that have had a profound influence on us. I think of these as portal books. A gate is a public entrance, a way in that everyone is aware of. Some of us may choose not to enter, but there’s no denying its renown. It’s there for everyone to see, bold and unforgettable. Like Babylon’s Ishtar Gate or the Golden Gate of Byzantium or the Meridian Gate to the Forbidden City. But whereas a gateway is public, drawing attention to itself, portals are hidden, only visible to the few—and that’s often where the truly profound magic lies. It’s these sorts of books that reveal most about us. While gateway books are those we share with others, portal books are more personal—they divulge our uniqueness. We rarely talk about them because others will most likely not have read, or even heard of, them.  One of my portal books was so buried in my past I couldn’t even remember the name of it. (By coincidence, it also featured a type of portal as a plot device.) It was by British author E (Edith) Nesbit. Her most famous novel is The Railway Children, but this well-known book had little impact on me and I barely remember reading it. At around age eleven I scoured my local library for E Nesbit books. I found many of them a little disturbing. She didn’t write like the other authors I’d read. There was an edge to it I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Perhaps I’d now call it a hint of the grotesque, a slightly off-kilter frisson. The novel I remember most powerfully, the one that I would nominate as my key portal book, was about a dirt-poor crippled orphan boy in Edwardian London who mysteriously travels to an alternative world 300 years earlier where he’s a healthy son of a nobleman. The story didn’t pivot around predictable plotlines. I haven’t re-read it since, but I remember the boy moved between the two periods several times until it got to a point where he had to make a choice. I remember being floored by his freely-made decision to stay in the world where he was dirt-poor and crippled because he was needed there. The novel was called Harding’s Luck. It’s usually relatively easy to pinpoint how gateway novels have affected you. The influence of portal books, by their nature, is harder to tie down. I’ve only recently realised the connection between this book and my latest novel, which while having a totally different setting, structure and feel to Harding’s Luck, is about portals and the crucial decisions they force on people. I don’t expect too many of you to have read Harding’s Luck, and I suspect its life as a potential portal book is over. Younger readers these days will probably baulk at the Edwardian street language, and for those of us older readers, the time for gates and portals into reading will never return. You can quite easily find Harding’s Luck online these days. But of course, it doesn’t matter whether or not you’ve read it. You all found your own portals. This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #115.  So how does fantasy & science fiction compare to other fiction genres? Is its popularity trending up or down? My hunch based on my experiences in the industry would have been it was in the top two (or maybe three) most popular genres—but then I could be biased in my thinking because I write speculative fiction, read more speculative fiction than any other genre, and co-edit the speculative fiction magazine, Aurealis. I’m in contact with like-minded people daily. It’s easy to over-emphasise how widespread something is under those circumstances. Hunches are all well and good, but I decided to hunt up some recent statistics. It proved quite tricky to do. A survey of US readers by Statista last year asked people which genres they read regularly. These were the results. As you can see, people could nominate more than one genre. Crime & Thriller 59% Adventure 47% Classics 44% Fantasy 43% Historic 42% Romance 42% Science Fiction 42% Literature 40% Horror 26% Erotica 12% Other 8% Don’t know 1% I don’t have access to the methodology or raw data behind this, but what struck me was that the top genre ‘Crime & Thriller’ was the only ‘double-barrelled’ category in the survey. I suppose it’s a natural association to combine the crime genre with the thriller genre, even though not every crime novel is a thriller, and not every thriller is a crime novel. However, wouldn’t the combining of fantasy & science fiction into one category for the purposes of this survey have been at least as natural? Most of the bookstores I’ve been to over the years pair the two. It’s been argued by some that fantasy & science fiction are both part of the continuum of speculative genre fiction. Others have maintained that genres should be defined by the primary emotion they intend to evoke, and that both fantasy & science fiction are part of what should be called the Wonder Genre. There’s even a line of argument that science fiction is actually a subset of fantasy. Whatever, the case, the two are clearly closely linked. So what would the result have been if they had been classed as the one ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ category within the survey. Clearly, since the respondents were allowed to give more than one answer, you can’t simply add the two percentages together, but there’s no doubt combining the two results would have changed the results considerably, most likely putting ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ at number two, possibly even number one. It all comes down to how many people in the survey said they read science fiction regularly but not fantasy and vice versa. 2017 survey by the Australia Council for the Arts and Macquarie University gives us some insight into the relative popularity of a combined ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ category. In this survey, people were asked to nominate their number one favourite adult fiction genre (that is, they couldn’t list more than one, so we can’t compare it directly to the Statista survey). Their results were as follows: Crime/Mystery/Thrillers 32% Science Fiction & Fantasy 22% Contemporary/General Fiction 14% Romance 7% Historical 6% Classics 6% Literary 3% Graphic Novels, Manga & Comics 3% Horror 2% Erotica 2% This one has a triple-barrelled category as the most popular. Interestingly, it focused solely on adult fiction titles, so it deliberately excluded Young Adult/New Adult titles which are often also read by adults and which have a high proportion of fantasy & science fiction titles. It’s usually worth digging past the headlines of a statistical-based announcement. Statistics are incredible useful and a crucial part of modern life, but they can be misleading if they are naively interpreted. For example, industry statistics and publishing professionals have been reporting for years that since 2010 print sales for fantasy & science fiction have halved.

This belief was debunked at the 2018 SFWA Nebula Conference in a presentation based on data collected by www.authorearnings.com. It provided evidence that when ebooks and audio books are taken into account, traditional publishers are currently selling more adult fantasy & science fiction than ever before. Furthermore, in 2017, 48% of fantasy & science fiction bought in the US were non-traditionally published books. So in reality, instead of fantasy & science fiction numbers halving since 2010, as is often claimed, they have in fact doubled. Just to add further evidence that there’s a boom in fantasy & science fiction, in 2018 Aurealis magazine has had its most successful year since going digital-only with a 41% increase in paying subscribers. Here's to the boom! This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #116. For those of you who don't know, I co-edit a fantasy and science fiction magazine called Aurealis. A number of years ago, when Aurealis was a print-only magazine, we regularly applied for grants from various government bodies such as the Australia Council and Arts Victoria. We were competing for funding with well-established literary magazines such as Meanjin, Overland and Quadrant. The funding always went directly to increasing author payment levels, so we felt it was worth the effort. It was always a difficult and time-consuming process to fulfil all the requirements of an application. We were successful on five occasions, but we also had a long string of unsuccessful applications. The biggest sticking point was always the requirement to demonstrate ‘literary merit.’ Surely only a reading of the stories can demonstrate that.

But that’s where a magazine of fantasy and science fiction is at a distinct disadvantage. At the end of 2017 the results of a research project called The Genre Effect study were published in the journal Scientific Study of Literature. It was undertaken by Professors Chris Gavaler and Dan Johnson from Washington and Lee University. Around 150 participants were given a text of 1000 words to read. Half were given a ‘literary’ version of the text and the other a ‘science fiction’ version. The texts were identical except in the literary version, the main character enters a diner while in the science fiction version, he enters a galley in a space station inhabited by aliens and androids as well as humans. The only differences between the two were setting-related. For example, the literary version used the word ‘door’ and the science fiction version used the word ‘airlock.’ After the reading, the participants were asked to comment on the literary merit of the story they had read. They were asked how much effort they spent trying to work out what the characters were feeling, and how much they agreed with statements such as ‘I felt like I could put myself in the shoes of the character in the story.’ The study exposed a self-fulfilling bias among literary readers against science fiction, demonstrating that science fiction is currently still unfairly viewed in academia. Here are some of the results from the study: ‘Converting the text’s world to science fiction dramatically reduced perceptions of literary quality, despite the fact participants were reading the same story in terms of plot and character relationships.’ The readers of the science fiction version generally scored lower in comprehension. They ‘reported exerting greater effort to understand the world of the story, but less effort to understand the minds of the characters.’ The professors also reported that readers of the science fiction version of the story ‘appear to have expected an overall simpler story to comprehend, an expectation that overrode the actual qualities of the story itself… the science fiction setting triggered poorer overall reading and appears to predispose readers to a less effortful and comprehending mode of reading—or what we might term non-literary reading—regardless of the actual intrinsic difficulty of the text.’ Professor Gavaler says, ‘those who are biased against SF, thinking of it as an inferior genre of fiction, they assume the story will be less worthwhile, one that doesn’t require or reward careful reading, and so they read less attentively… It’s a self-fulfilling bias—except we can now show objectively that the weakness is with the reader, not the story itself.’ He adds, ‘if you’re stupid enough to be biased against SF you will read SF stupidly.’ He is interested in exploring this Genre Effect further and discovering whether fantasy tropes such as a sorcerer’s wand would have similar effects on readers. These results are not a surprise to those of us who have been involved in science fiction publishing over the years and explains the issues we had when applying for grants in the past. As Professor Gavaler says, while it’s disappointing that these biases exist, at least now they’ve been exposed. A version of this article appeared in Aurealis #114. I was on a panel at Speculate, the Speculative Writers Festival, earlier this year ambitiously titled ‘Science Fiction: The Past, the Present, and What’s to Come’. I was charged with presenting a 10-minute introduction to the present trends in science fiction. It proved quite a challenge to wrestle the vast amorphous mass that is the science fiction currently being written into some recognisable pattern. The days have long gone when a single person could read even a sizeable percentage of all the science fiction produced in a calendar year. And making the task even more difficult was the fact that trends are usually only clear in retrospect. Nevertheless I gave it a go. Because of the panel’s specific focus and the nature of the festival audience—and to try to make the task slightly more manageable—I concentrated specifically on what could be fairly unambiguously defined as science fiction as opposed to fantasy, on the written word rather than movies and television series, and on novels rather than short stories. Since the festival was aimed at writers of speculative fiction, I looked for patterns in what was big in the science fiction of today—what was hitting the bestsellers lists and what was winning awards. So what big trends did I uncover? There were four.  The first was Climate Fiction, that is, fiction that deals with climate change, often in a post-apocalyptic or dystopian future. The interesting thing about cli-fi, to use the slightly dismissive abbreviation commonly used, is that it is taken seriously by the mainstream. The literary establishment has embraced it, and it gets reviewed in the mainstream press. People base their PhDs on it. It has status as ‘literature’ and isn’t dismissed the way a lot of science fiction still is. While the literary establishment has recently discovered cli-fi and bestowed a sense of worthiness on it, Climate Fiction has, of course, been around for some time as part of the science fiction landscape. Australian author George Turner wrote the quintessential cli-fi novel well before it was a recognised subgenre of science fiction. His The Sea and Summer (The Drowning Towers in the US) was set in a world where global warming had resulted in a Melbourne landscape that was largely underwater. It was published in 1987 and won the Arthur C Clarke Award and was nominated for a Nebula. Climate Fiction is making an impact in the major SF awards. Out of the six Hugo Finalists for Best Novel this year, two were clearly cli-fi: New York 2140, by Kim Stanley Robinson and The Stone Sky, by N K Jemisin (technically science fantasy). Other major Climate Fiction novels in recent years include Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife. Three recent Aurealis Awards Finalists also fall into the category: Clade by James Bradley, Lotus Blue by Cat Sparks, and Daniel Findlay’s Year of the Orphan. The second trend was the New Space Opera. ‘Space opera’ was originally a somewhat disparaging name, deriving from a comparison with ‘soap operas’ and suggesting grand, melodramatic themes. It involved large-scale, fast-paced science fiction adventure featuring space warfare, alien races and intelligent machines. Often it had a military aspect to it, although the main character focus was on civilians. Brian Aldiss once said, ‘Science fiction is for real, space opera is for fun.’ The New Space Opera is still fun on a grand scale, set in space, exciting, fast-paced, but it’s also usually more scientifically rigorous, more literary, has more emphasis on character development, and addresses social issues of race, gender, class and postcolonialism. The term was coined in the 2007 anthology The New Space Opera edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan. Notable novels that fall into this subgenre are Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice winner of the 2014 Hugo Best Novel, Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion, Yoon Ha Lee’s The Raven Stratagem, a Best Novel Finalist in this year’s Hugos, and The Expanse series by James S A Corey. The New Space Opera has also been invading Young Adult books with such novels as Illuminae by Amie Kaufman and Jay Kristoff, the 2015 Aurealis Award Best SF novel winner.  The third trend I identified was Generation Ship Fiction which focuses on sub-lightspeed starships that take several human generations to arrive at their destination, where the original occupants grow old and die, leaving their descendants to continue travelling. Unlike works relying on faster-than-light (FTL) travel, this subgenre is based on the more rigorous extrapolation of current science where FTL speed is impossible. The closed environment of a generation ship has proven to be a particularly versatile story vehicle, allowing powerful explorations, ranging from sustainability-based dilemmas and breakdowns in social structures to murder mysteries. Recent examples include Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson, Neal Stephenson’s SevenEves, and Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty, a 2018 Hugo Best Novel Finalist.  Gender-focused Science Fiction was the fourth trend I found. These works deal with gender identity and involve depictions of single gender or genderless societies. Like all the other trends, it’s not new, but it has become increasingly prominent in recent times. It’s a trend that is often combined with one of the other three trends. The obvious precursor is the multi-award winning The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin, published in 1969. Two New Space Opera novels I’ve already mentioned clearly also fall into this subgenre: Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion and Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice. Recent Australian Gender-focused Science Fiction has included From the Wreck by Jane Rawson, which won the 2017 Aurealis Awards for Best SF Novel and An Uncertain Grace by Krissy Kneen, which was an Aurealis Awards Finalist in the same year. Of course, for writers, identifying trends isn’t much more than the first step. The crucial question is to what extent (if at all) should a writer take these trends into account. That’s something to explore another time. This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #113. |

AuthorDirk's a writer, editor and publisher of science fiction, fantasy and horror Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed